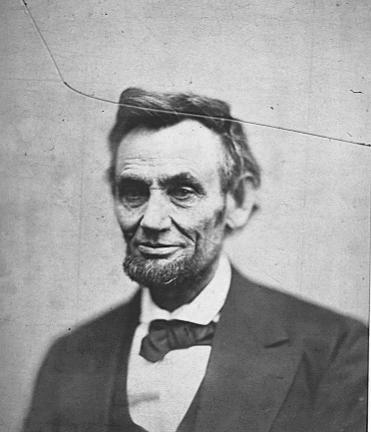

Of course, he would've hated me saying that, since Abraham Lincoln hated being called 'Abe.'

Of course, he would've hated me saying that, since Abraham Lincoln hated being called 'Abe.'Today marks the 200th birthday of the legendary Abraham Lincoln. In many ways it seems surreal; Lincoln has been sainted into the American pantheon, so like George Washington, Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and all their kin, he has become more of an idea and a model than a mere mortal.

The real Abraham Lincoln is worth learning about. It's easy to find a book and really any part of his life. Some are simply a work in hagiography; some are honest dives into his many and frequent contradictions. The best place to start, I would say, is where his fame began--the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates. Many people forget that (i) the debates were simply between two Senate candidates from the small frontier state of Illinois, and (ii) Lincoln lost that election (not by popular vote; Democrats won in the state legislature and voted to send Douglas to the Senate, since it was before the passage of the 17th amendment), though two years later, he managed to win the presidency in an electoral landslide against the same Stephen Douglas that he had lost to before.

From the outset, Lincoln's presidency was a constant crisis, only beginning to settle a week before he was killed. Upon his election, a number of Southern states rejected the outcome, choosing to secede from the Union rather than be under a country run by an 'abolitionist' (though, at the time, Lincoln would not have put himself in that camp). When he took the oath of office on March 4, 1861, he reached out to Southerners, reminding them that

In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to 'preserve, protect, and defend it.'

Aggress they did, and for four bloody years, over 600,000 Americans perished. Lincoln was known for the pain he suffered at the losses and for the happiness he took in sparing some from it; in one story, a woman came to the White House, begging him to grant her son, a deserter from the Union Army, clemency, which he immediately did, saying "I think this boy can do us more good above ground than under it." He educated himself quickly on the matters of war and strategy, constantly struggling with his generals. From the pompous and ineffective George McClellan (who would unsuccessfully challenge him in 1864 for the presidency) to the inept John Pope (whose famous statement, "my headquarters are in the saddle," was met with Lincoln's retort that "The problem with General Pope is that his headquarters are where his hindquarters ought to be"), Lincoln struggled to find a military leader capable of achieving his aims: full Union, and, only later, emancipation. He found his man in later 1863, with the rise of General Ulysses S. Grant.

Ultimately, the Civil War was won, and Lincoln was vindicated. A week after General Lee's surrender to General Grant at Appomattox, Lincoln, having visited the conquered Confrederate capital of Richmond a few days before, took an evening to see the play, Our American Cousin, at Ford's Theater in Washington. Halfway through the second act, the famous stage actor, John Wilkes Booth, burst forth into Lincoln's private box, shot the president, and lunged to the stage, snagging his stirrup on the drapes of the balcony and breaking his leg. He shouted "Sic Semper Tyrannis!", the motto of Virginia (meaning "thus always to tyrants!") and ran off the stage. Lincoln never regained consciousness. The next morning, at 7:22am, he passed away in the bed of the Peterson house, across the street from the theatre, with his large legs hanging over the edge of the all-too-short bed. The Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, looked at the clock, which was opened and stopped, and said somberly "Now he belongs to the ages."

Lincoln's effect on the United States was greater than any president, before or since, with the possible exception of George Washington. The country in which he grew up was uncentralized, State-run, half slave and half free, backwoods, and brand new. The country he left spewed forth power from Washington, had dramatically settled a major Constitutional quandry, been made fully free, and was on the course to become, in less than 50 years, one of the most powerful players in the world. He helped establish the modern laws of war. He sought to be sure that the North was a victor but not a conqueror. He desired reconciliation. Most importantly, he was led by the ideas that had founded the nation and which still lead us today. The Founders, he believed,

intended to include all men, but they did not mean to declare all men equal in all respects. They did not mean to say all men were equal in color, size, intellect, moral development or social capacity. They defined with tolerable distinctness in what they did consider all men created equal — equal in certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness ... They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society which should be familiar to all: constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even, though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people, of all colors, every where.

Abraham Lincoln was deeply flawed, as are all people, but managed to be the perfect man in our nation's most desperate hour. It's good that we remember his birthday and celebrate his achievements. The man has become myth, but I think, like the myths of Washington and Franklin, of Roosevelt and Kennedy, it is important for us to hold onto. The American psyche looks for leaders who were strong and selfless, who were introspective and extroverted. We celebrate those who met scorn in office but were vindicated after. We mourn the loss of those who weren't able to complete the work that they had "thus far so nobly advanced". He was a remarkable man, and today I wish him the happiest of birthdays.

No comments:

Post a Comment